Sometimes the most fleeting oversight, the most trivial error can permanently damn a creative project. In 1968, George Romero’s distributor declared that his creepy black-and-white film Night of the Flesh Eaters had a title too similar to another film (1964’s The Flesh Eaters). Romero agreed to retitle it Night of the Living Dead, but the lackey in the distributors’ office responsible for splicing in the new title inadvertently removed the copyright declaration frames entirely. It was years later that Romero and his fellow producers Russo and Streiner were made aware that the loophole was being exploited and the movie was being treated as a public domain work, distributed and screened without any permission or payment whatsoever. This was no brief heartbreak. The ensuing frustrated efforts to incontrovertibly reclaim the legal rights to the film spanned decades, culminating in 1990 with what Russo, Romero and Streiner hoped would be the final measure: remake the movie. They were mistaken. (Russo had the balls to try again in 1999 with his independently conceived and justifiably maligned “30th Anniversary Edition” featuring new scenes and music.) Here we are twenty years later with the issue still unresolved. These three men will likely go to their graves without the satisfaction of having the rights to their property returned, never mind the accompanying owed revenues.

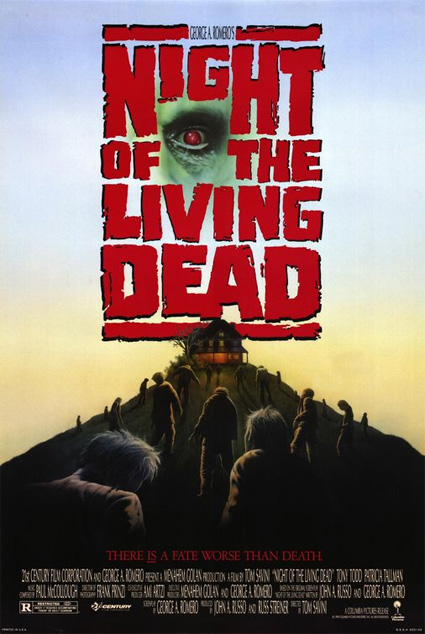

As a legal maneuver, Night of the Living Dead (1990) failed utterly. As a film, it is remarkably effective and a beautiful turn in George’s legacy, yet largely dismissed and forgotten by audiences.

Romero penned the script, incorporating creative divergences from Night ’68, playing with audience expectations and bringing the gender politics up to date. He was the obvious choice to direct but, unfortunately (or fortunately), he was contracted to film The Dark Half and couldn’t commit to Night ’90. As with most of Romero’s productions, a compromise proved a serendipitous boon. In this case, with Romero unavailable, goremaster Tom Savini assumed the responsibility instead, making this his first full-length directorial effort.

Romero was intensely involved in production, and is even rumored to have directed some scenes. Some other scuttlebutt has it that Romero supported and protected Savini and that, whenever he had to leave the set, Streiner and Russo stopped cooperating with Savini, hobbling the execution of his vision even to a further degree than the $4,000,000 budget already had. As Savini said in a 2004 interview, “it’s only about thirty to forty percent of what I intended to do.” (While it’s hard to imagine a fluke benefit to sabotage, perhaps we can be grateful that Savini never got to make the opening moments black-and-white, transitioning to sepia and finally full-color, or to give Barbara hallucinations of her dead mother as a zombie, as revealed by his original storyboards.)

Romero was intensely involved in production, and is even rumored to have directed some scenes. Some other scuttlebutt has it that Romero supported and protected Savini and that, whenever he had to leave the set, Streiner and Russo stopped cooperating with Savini, hobbling the execution of his vision even to a further degree than the $4,000,000 budget already had. As Savini said in a 2004 interview, “it’s only about thirty to forty percent of what I intended to do.” (While it’s hard to imagine a fluke benefit to sabotage, perhaps we can be grateful that Savini never got to make the opening moments black-and-white, transitioning to sepia and finally full-color, or to give Barbara hallucinations of her dead mother as a zombie, as revealed by his original storyboards.)

However, there was a definite silver lining effect to other shortfalls. With such a paltry production budget, it’s clear that little was set aside for a score. Composed and performed entirely by one man armed only with synthesizers (Paul McCullough, screenwriter for Romero’s 1973 virus-panic flick The Crazies, widely considered the test run for Dawn of the Dead), the score sounds very strange and instantly dated. Off-putting. Jarring. In short, it’s wholly weird and effective. A similar strangeness occurred when the sky failed to produce menacing stormclouds and Savini was forced to shoot the opening cemetery attack scenes in glorious full sun. The result is an eerie juxtaposition, a sterling example of daylight horror.

While the daylit cemetery scene was a happy accident, the rest of the cinematography is expert, with the lighting in particular being sublimely plotted. It is all immensely contrived: hard-to-place “kickers” make characters’ silhouettes stand out, and other great pains result in lighting that looks… completely natural. The daytime interiors are created with sunlight-like cool diffusion, the nighttime exteriors are adequately vast and dark, and the interior of the farmhouse at night seems to be lit only by a bunch of shitty incandescent bulbs. The best thing that can be said about these elaborate lighting schemes is that you will never notice them.

While the daylit cemetery scene was a happy accident, the rest of the cinematography is expert, with the lighting in particular being sublimely plotted. It is all immensely contrived: hard-to-place “kickers” make characters’ silhouettes stand out, and other great pains result in lighting that looks… completely natural. The daytime interiors are created with sunlight-like cool diffusion, the nighttime exteriors are adequately vast and dark, and the interior of the farmhouse at night seems to be lit only by a bunch of shitty incandescent bulbs. The best thing that can be said about these elaborate lighting schemes is that you will never notice them.

One of the best elements of the film was not the result of crap luck, or luck at all—FX guru Savini made the remarkably wise and humble decision to delegate all of the zombie makeup work to the talented Optic Nerve team. They knocked these zombies out of the park. With little exception, they are at once both realistically rendered—bloated and discolored in accordance with actual decomposition—and hauntingly blank. The only missteps are a couple of dummies who are betrayed by too many seconds of revealing screen time; their rubbery nature becomes increasingly obvious in repeat viewings. (If you enjoy the movie enough to rewatch it, it’s hardly a dealbreaker.)

The supporting cast, likewise rubbery dummies with too much screen time, are just as hard to watch. The main cast, however, is magnificent—Patricia Tallman as Barbara, Bill Mosely as Johnny, Tony Todd as Ben, and Tom Towles as Harry (a role originally given to Ed Harris, who chose to drop out—another bit of bad luck to be grateful for, since Towles is insanely fun). Mosely does his fabulous character-actor bit and then bites the dust. Tallman, Todd, and Towles survive and cook up an intense chemistry, a heady blend of distrust, desperation, and shouting.

The supporting cast, likewise rubbery dummies with too much screen time, are just as hard to watch. The main cast, however, is magnificent—Patricia Tallman as Barbara, Bill Mosely as Johnny, Tony Todd as Ben, and Tom Towles as Harry (a role originally given to Ed Harris, who chose to drop out—another bit of bad luck to be grateful for, since Towles is insanely fun). Mosely does his fabulous character-actor bit and then bites the dust. Tallman, Todd, and Towles survive and cook up an intense chemistry, a heady blend of distrust, desperation, and shouting.

Acting is not Tallman’s strongest suit (she’s a stunt performer by trade), but her occasional stiffness works well for all of Barbara’s phases, reading as either nervousness or posturing. Her character evolves in sudden moves—each one reflected in a wardrobe change—playing out like a condensed combination of all the female leads from Romero’s original Dead trilogy.

First you have classic Barbara, as meek, proper, and fussy as she is in the original Night of the Living Dead. As she processes the horrors around her, she becomes more like Fran from Dawn of the Dead, withdrawn at first but fighting to be cool-headed and proactive. By the end, she’s most like Sarah from Day of the Dead, totally in control, boss and laid-back, at ease with a gun, smirking with an edge of misanthropy—totally acclimated to survive in this awful new world. She survives where the original Barbara perished in her weakness and inability to deal. Barbara’s new arc, as well as the other story changes, demonstrate a tremendous script with remarkable updates by Romero. While of course it can’t supplant the original 1968 film, it’s arguable that Night ’90’s greatest value is in the ways it shifts, improves, comments on, and complements the original.

First you have classic Barbara, as meek, proper, and fussy as she is in the original Night of the Living Dead. As she processes the horrors around her, she becomes more like Fran from Dawn of the Dead, withdrawn at first but fighting to be cool-headed and proactive. By the end, she’s most like Sarah from Day of the Dead, totally in control, boss and laid-back, at ease with a gun, smirking with an edge of misanthropy—totally acclimated to survive in this awful new world. She survives where the original Barbara perished in her weakness and inability to deal. Barbara’s new arc, as well as the other story changes, demonstrate a tremendous script with remarkable updates by Romero. While of course it can’t supplant the original 1968 film, it’s arguable that Night ’90’s greatest value is in the ways it shifts, improves, comments on, and complements the original.

How could such a good movie come out of terrible motives, one absentee director, one untested substitute director, tampering producers, and a low-to-middling budget?

Perhaps more interestingly, why was it rejected? It seems to never come up in conversation. We’re one month away from the twentieth anniversary, yet there is no Blu-Ray release in sight, and the one and only DVD release was back in 1999.

The reasons behind it being so despised remain mysterious to me, but it might be as simple as punishment for flouting fan expectations—perhaps Savini’s and Romero’s names were simply in the wrong places. At the time, many viewers expected more gore from Savini, but where does one go from Day of the Dead? It’s nearly untoppable. It’s taken fans a long time to come around from clinging to the articles of faith that only Romero could direct a Romero movie and only Savini could make a Savini zombie. Many Romero fans have come to embrace this movie bit by bit, perhaps out of disappointment with his more recent movies, in which, being rightfully lifted up by the surge of zombie popularity, he has enjoyed better budgets and creative carte blanche. After all, Romero originally became acclaimed for movies with shoestring budgets and other handicaps—he seemed to thrive when restrained. The Night of the Living Dead remake may be the last movie to fit these conditions and, in many ways, it outshines Romero’s more recent zombie pictures. As long as we’re making the effort to go see new Romero pictures, might as well do ourselves a favor and give a new watch to Savini’s Romero picture.

Julia Sevin is a the co-owner and co-editor of Creeping Hemlock Press, a New Orleans-based specialty press offering fine limited editions of tasty genre books, culminating with Print Is Dead, an upcoming line of zombie novels. Her fiction appears in the anthologies The Living Dead 2 (ed. John Joseph Adams) and Bits of the Dead (ed. Keith Gouveia). “Thin Them Out,” the story from The Living Dead 2, co-written with R.J. Sevin and Kim Paffenroth (Dying to Live, Gospel of the Dead) was originally released through Creeping Hemlock Press as a $6 signed/limited chapbook for the 2008 Zombie Fest in Monroeville and is available for purchase at creepinghemlock.com. Julia grew up in the coastal Northern California hamlet of Mendocino, which was far too clean and safe an environment to be conducive to writing zombie fiction. New Orleans is much better for it, and a cultural and culinary mecca to boot.